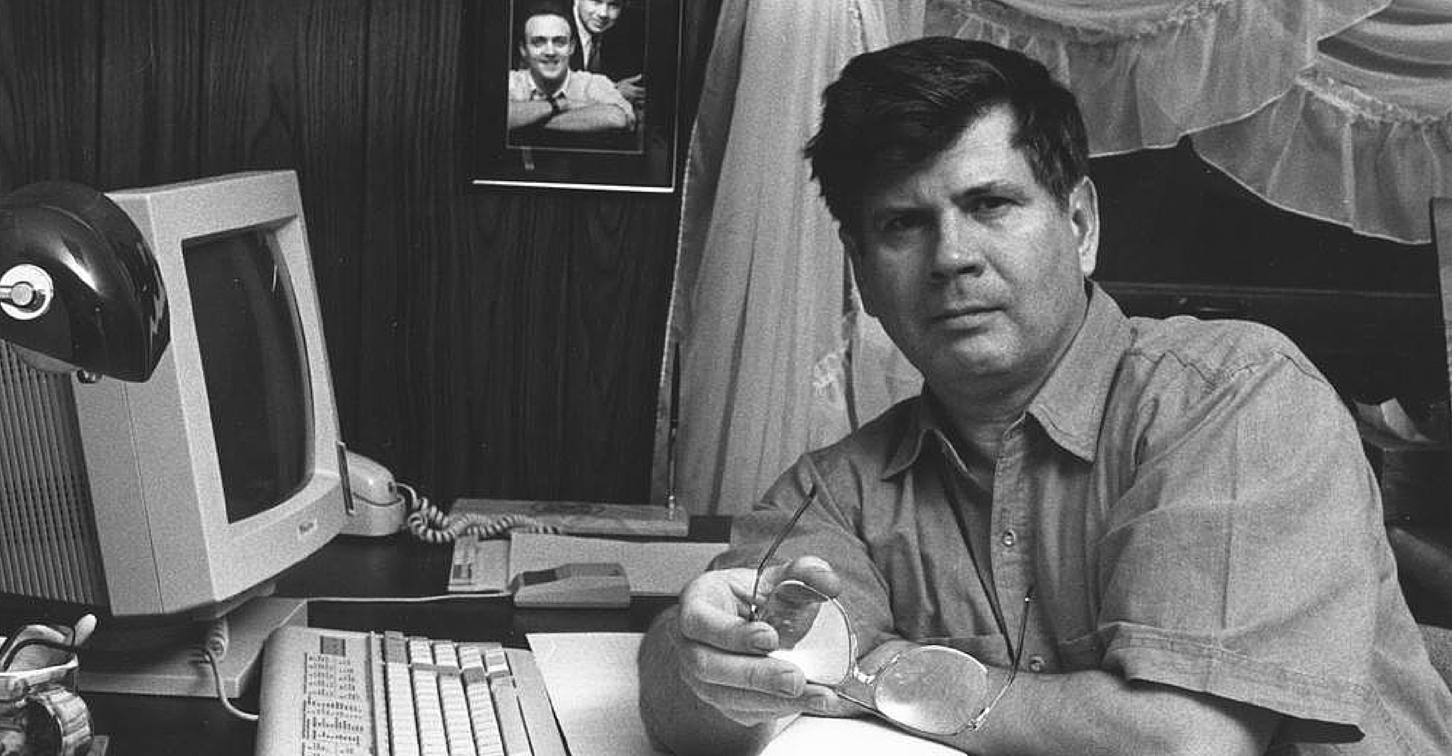

Me and Bill

April 30, 2015

by Mark Dunning

Bill Kimberling is a man with stories. Hundreds of stories. Thousands of stories. All of them your stories. He compiled them over decades of working with Usher syndrome families. The data, the bland details, are cataloged in wrinkled medical records stuffed in thick manila folders. The good stuff, the touching, the compelling, the inspiring, well, that he keeps locked safely in his heart.

In honor of the dedication of the William J. Kimberling Usher Research Laboratory at the University of Iowa, I ask you, I implore you, to take a few moments and share your stories of Bill. You can write them in the comments or send them in an email to me at m.dunning@lek.com. I know your words will spark his memory and warm his heart. This is my story.

Bill Kimberling could not understand why I would want to travel all the way to Iowa to see him. I was welcome, of course. Everyone was always welcome, but Bill was too humble to think the trip would add much value. “If you really want to see cornfields,” he said, “we’ll be happy to have you.”

This was Dr. William Kimberling, mind you. The world’s leading expert on Usher syndrome. My journey to find someone, anyone, who knew Usher syndrome was destined to end with Dr. Kimberling. He was the one name that came up over and over and over as I skipped from doctor to doctor looking for a way to save my daughter’s vision. If anyone would know, it was Dr. William Kimberling.

He stood on a pedestal in my mind, the Usher Oracle of Omaha, the man who had made first Boystown Hospital, then the University of Iowa, the center of Usher syndrome expertise merely by his presence. I expected a man larger than life, stuffed full of himself, a finger-waving father figure armed with an unbending way of doing things forged over decades of experience. Yet he answered his own phone. He made his own appointments. He asked me what time worked best for me. He would work around my schedule. Just what kind of doctor was this Dr. Kimberling? He didn’t sound intimidating at all.

He wasn’t. He introduced himself as Bill. We met in the bright, modern, openness of what was called the Carver Laboratory at the University of Iowa. There were long hallways of smooth cement, tall glass, and polished metal. Our voices echoed. Bill shook eight year old Bella’s hand and that of five year old Jack. He apologized for inconveniencing us with the long drive.

It was stiff and uncomfortable at first. Small talk wasn’t Bill’s strength. He gave us a tour but he didn’t know the purpose of many of the rooms. There were no other humans to be found. It felt like we had the entire multimillion-dollar research facility to ourselves. Jack skipped ahead. Bella wobbled close by.

After several rooms of beakers and pipettes, we came to an office with desks and pictures and, if memory serves, planes hanging from strings. Bill introduced us to the Director of the Carver Family Center for Macular Degeneration, Howard Hughes Medical Investigator, and Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. The man towered, his head tipping the dangling planes. His hands were like bear paws. His cavernous voice seemed to generate somewhere in his shoes and roll through him like notes in a pipe organ. This, this was a doctor! As his hand swallowed mine he introduced himself.

His name was Ed.

Just Ed.

Bill and Ed led us to a large room lined with work benches and crowded with complex looking equipment. The Iowa sun poured in through tall windows and tossed angular shadows about. The ceilings were high. It felt nothing like a hospital yet Ed examined Bella’s eyes just the same. He rolled the equipment to her. When he spoke, Ed spoke to Bella, as if she were the most important person in the room. Bill shuffled in the background and fumbled uncomfortably with small talk.

When the examination was done, Bill and Ed asked if we had any questions. We had one.

How long?

That’s when Bill casually saved my life.

He transformed before us. Gone was the humble man who looked at his shoes and struggled with idle banter. He grew in stature and confidence, nearly bubbling with excitement. It was time to talk Usher syndrome. It was time to talk family. Bill was finally in his element.

“Oh, she’ll be fine,” he said in his mid-west tone, waving his hand enthusiastically,

“She’ll have plenty of vision to get through college and beyond.”

He said it so matter-of-fact, so conversationally, that it took a moment to register. There was no pretention or condescension. It wasn’t a lecture. The clock on the wall didn’t matter. It felt like we were sitting at a picnic table with a red checked table cloth, eating potato salad, talking about Aunt Edna’s gout and Bella’s Usher syndrome. He spoke of Bella as a person. He spoke of Bella functioning in the real world. This was Usher syndrome for families. This was Usher syndrome with families. This wasn’t how doctors spoke. This wasn’t what doctors said. But it was exactly what I needed to hear.

Suddenly Bella had a future. She wasn’t going to be blind tomorrow. She wasn’t going to grow up in darkness, isolated from society, reading textbooks in braille. She was going to get an education, grow in to an adult, meet some guy and fall in love. She was going to live. Usher syndrome was no longer a death sentence.

I dropped so much ballast that I nearly floated to the high ceilings with relief. I wanted to jump on the table and tap dance among the glassware. A strange, distantly familiar sensation tugged at my cheeks and I realized I was smiling. Finally, I had a reason to smile.

After casually, humbly saving my life, Bill then proceeded to change it.

I was so grateful for all he had said that I asked if there was anything I could do to help him. I was just some dumb parent. I expected the stock answer of just keep in touch with us or maybe write us a check. But that wasn’t Bill.

“I have this study I have been thinking of doing,” he said, “Do you want to help?”

Wait? What? I still shake my head in disbelief all these years later. It was like it was Saturday afternoon and he was going off to rake leaves. “I have another rake. Do you want to help?”

Yes! Yes, I wanted to help. My God, I wanted to help. I wanted to do something, anything, to help my daughter. But to be treated as an equal? As a valuable contributor? That changed everything for me. That changed my life.

It started with a few phone calls with Bill. Heidi and Marly joined, too. And me. Mark. The four of us. I knew nothing, but that didn’t matter to Bill. He liked to talk Usher syndrome. He liked to talk about it in broad strokes and tiny details and he liked more than anything to teach Usher syndrome. So I learned about Usher syndrome. But most importantly I learned that I could learn. With a patient teacher, I could learn the broad strokes and the tiny details. I could contribute. I could be a partner

This dumb parent, me, Mark, I could save my daughter. I could change the world.

That was it. That was the beginning of the Usher Syndrome Coalition, right there in Iowa with Bill and Ed. And, I guess, Mark and Bella and Julia and Jack.

I am fortunate enough to have counted Bill among my friends for a long time now. I have other stories of him that I would be happy to share. But they all have the same theme. Bill bashfully welcoming me, asking me to join him, as an equal, as a partner, in changing the world for people with Usher.

So that’s my story of Bill. I can’t wait to hear yours. Please send them, long or short, a sentence or pages. We’ll include them as part of the dedication ceremony of the new William J. Kimberling Usher Research Laboratory at the Wynn Institute for Vision Research at the University of Iowa. But more importantly, we will pass them on to Bill. There is still nothing he enjoys more than hearing from Usher families.